The present value formula has become essential for anyone involved in financial planning, investment analysis, or business valuation. When you examine this formula closely, one variable stands out as particularly important—the exponent. Understanding what the exponent represents, how it works, and why it matters can transform your ability to make informed financial decisions that align with your long-term goals.

This comprehensive guide breaks down the exponent in the present value formula and demonstrates how this seemingly small mathematical element controls the entire calculation. Whether you’re analyzing investment opportunities, evaluating loan options, or planning for retirement, mastering this concept provides the foundation for confident financial management.

Understanding the Present Value Formula and Its Components

The present value formula serves as a bridge between today’s dollars and future dollars. It answers a fundamental financial question: what is the value today of money you’ll receive in the future?

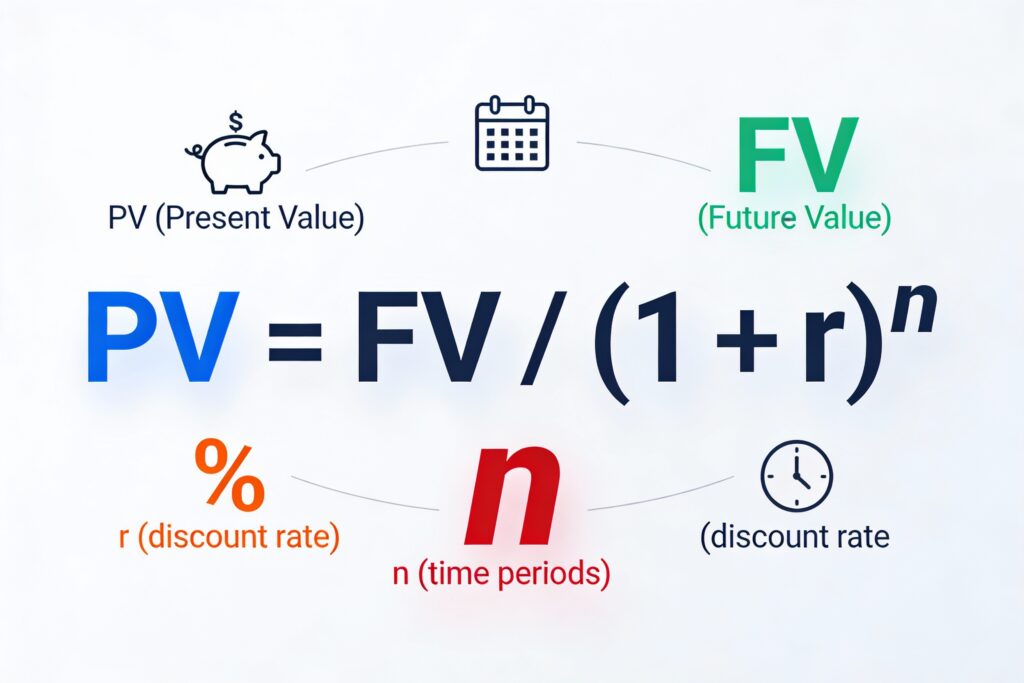

The standard formula reads:

PV = FV / (1 + r)^n

Each variable in this formula carries distinct meaning and importance. The future value (FV) represents the amount of money you expect to receive at a specified time in the future. The discount rate (r) reflects the interest rate or required rate of return—essentially the compensation you need for waiting and the risk you’re assuming. These components are well understood by most finance students and professionals.

The exponent (n), however, often receives less attention despite its critical role. This variable represents the number of time periods between now and when you receive the future cash flow. It might seem straightforward on the surface, yet this small mathematical indicator wields enormous influence over your present value calculations.

What the Exponent Represents: Number of Compounding Periods

The exponent in the present value formula (the variable n or t in different notations) specifically represents the total number of compounding periods over which your discount rate applies. When you see the expression (1 + r)^n, you’re looking at compound discounting—the mathematical process that accounts for the time value of money.

Think of it this way: the exponent tells you how many times the discount factor (1 + r) multiplies by itself. If you’re discounting a cash flow that occurs 5 years from today, and interest compounds annually, your exponent equals 5. Each year, the money loses value through the lens of present value calculation.

Time period matters enormously because the further away a cash flow exists in the future, the less valuable it appears in today’s dollars. A dollar you receive next year is worth more than a dollar you receive ten years from now—the exponent captures this time-based depreciation.

Consider real-world application: when a real estate investor evaluates whether to purchase a rental property, they must estimate rental income years into the future. The exponent in their present value calculations determines how aggressively they discount those distant cash flows. A larger exponent (farther into the future) produces a smaller present value, which might change whether the investment makes financial sense.

The Relationship Between the Exponent and Discount Rate

The exponent and discount rate work together in a mathematical partnership that determines present value. Neither operates independently—they interact to create the discount factor that transforms future dollars into today’s equivalent.

Consider two scenarios with identical future values and time periods but different discount rates. In the first, your discount rate is 5% annually. In the second, it’s 10% annually. The exponent remains constant at 5 years in both cases. Yet the resulting present values differ dramatically because (1 + 0.05)^5 produces a different outcome than (1 + 0.10)^5.

Similarly, if you keep the discount rate constant but increase the exponent, the present value decreases. A higher exponent magnifies the compounding effect of discounting. This mathematical relationship explains why long-term investments face greater uncertainty—the exponential function creates increasingly aggressive discounting as time extends further into the future.

Financial professionals carefully consider how changes in either the exponent or discount rate affect valuations. When evaluating a 20-year bond versus a 5-year bond with identical coupon rates, the exponent creates the primary valuation difference. The longer duration (higher exponent) produces lower present value for the same future cash flows.

How Time Periods Determine the Exponent Value

The exponent’s value depends entirely on how you define your time period and how frequently interest compounds. This distinction proves critical for accurate calculations.

If you’re using annual compounding and evaluating a cash flow that arrives 3 years from now, your exponent is 3. However, if interest compounds monthly, the same three-year period requires an exponent of 36 (12 months × 3 years). The nominal interest rate gets divided by the compounding frequency to maintain consistency, while the exponent increases proportionally.

Example: Suppose you invest $1,000 today and expect to receive $1,500 in 5 years, with a 7% annual discount rate.

Using annual compounding:

- FV = $1,500

- r = 0.07

- n = 5

- PV = $1,500 / (1.07)^5 = $1,500 / 1.4026 = $1,070.36

The exponent of 5 reflects the five annual periods. This result shows that receiving $1,500 five years from now is worth approximately $1,070 in today’s dollars, assuming a 7% opportunity cost.

If the same investment compounded monthly instead:

- The annual rate becomes 0.07/12 = 0.005833 per month

- The exponent becomes 5 × 12 = 60 months

- PV = $1,500 / (1.005833)^60 = $1,500 / 1.4191 = $1,057.41

Notice how more frequent compounding slightly increases present value, because you benefit from more compounding periods within the same timeframe.

Why the Exponent Creates Exponential Effects on Valuations

The term “exponent” exists because this variable determines exponential growth—or in the case of present value, exponential decline. This mathematical relationship produces non-linear effects that surprise many people encountering present value calculations for the first time.

Doubling the exponent doesn’t double the discount factor; it squares it. Tripling the exponent creates a cubic relationship. This exponential mathematics means that very small changes in the exponent can produce surprisingly large changes in present value when the discount rate is moderate to high.

Consider how a 6% discount rate affects different time periods:

- 1-year exponent: (1.06)^1 = 1.06

- 2-year exponent: (1.06)^2 = 1.1236

- 5-year exponent: (1.06)^5 = 1.3382

- 10-year exponent: (1.06)^10 = 1.7908

- 20-year exponent: (1.06)^20 = 3.2071

Notice how the discount factor doesn’t increase linearly with the exponent. A 20-year period creates more than three times the discount factor of a 10-year period. This exponential relationship explains why long-term investments in uncertain environments require significantly higher expected returns to justify their risk.

Investors and financial analysts use this understanding to recognize which investments warrant detailed analysis. A highly uncertain cash flow arriving 30 years from now contributes minimal present value, even if the nominal amount is substantial. This insight helps explain why early cash flows receive far more weight in investment decisions than distant ones.

Practical Applications: Investment Evaluation and Financial Planning

Understanding the exponent’s role transforms how you evaluate real-world financial decisions. Here’s how professionals apply this knowledge:

Retirement Planning: When calculating how much you need to save today to achieve a retirement goal, the exponent represents your years until retirement. A 30-year-old planning to retire at 65 uses an exponent of 35 years. This lengthy exponent means you need relatively little saved today, because those future contributions benefit from compound growth. Conversely, someone starting at 50 years old faces an exponent of only 15 years, requiring much larger annual contributions to reach the same retirement goal.

Bond Valuation: Bond investors compare bonds with different maturities using present value calculations. A 30-year Treasury bond faces a much higher exponent than a 2-year Treasury note. This extended exponent makes long-term bonds far more sensitive to interest rate changes, because altering the discount rate has multiplicative effects across 30 compounding periods rather than two.

Project Evaluation: Business managers use net present value (NPV) analysis to decide whether to undertake capital projects. The exponent varies for each year of the project’s cash flows. Early profits face small exponents (1, 2, 3) and contribute substantially to present value. Late profits face large exponents and contribute minimally. This reality encourages businesses to pursue projects that generate profit quickly.

Real Estate Investment: Property investors estimate future rental income, appreciation, and eventual sale proceeds. The exponent in their calculations determines which properties seem attractive. A property with strong near-term rental income (small exponent) often appears more valuable than one relying on distant appreciation (large exponent), even if nominal future cash flows are similar.

Common Mistakes When Working with the Present Value Exponent

Even experienced financial professionals occasionally stumble with exponent calculations. Recognizing these errors helps you avoid costly mistakes.

Period Mismatch: The most frequent error involves inconsistent time periods. If your interest rate is monthly but your exponent counts annual periods, or vice versa, your calculation becomes meaningless. Always ensure the interest rate’s compounding frequency matches your exponent’s time unit.

Forgetting to Adjust for Compounding Frequency: When interest compounds more frequently than annually, many people forget to adjust the interest rate. If an investment earns 12% annually but compounds monthly, you must use 1% monthly rates with 12× the number of periods for each year.

Misunderstanding Continuous Compounding: Some advanced applications use continuous compounding, where the formula becomes PV = FV × e^(-rt), using the mathematical constant e rather than the discrete (1 + r)^n approach. Confusing these approaches produces incorrect results.

Overlooking Partial Periods: Financial situations often don’t align perfectly with full years. If you need to discount a cash flow occurring 2.5 years from today, your exponent is 2.5, not 2 or 3. Rounding to the nearest whole number introduces avoidable errors.

Connecting Present Value to Your Financial Decisions

The exponent in the present value formula isn’t merely an academic concept—it directly impacts your financial future. By understanding how time periods affect valuations, you gain insight into why certain financial strategies succeed while others fail.

When comparing investment opportunities, remember that time represents both a blessing and a curse. Extra years allow compound growth, but they also create uncertainty and risk. The exponent captures this trade-off mathematically. Shorter investment horizons (smaller exponents) produce higher present values for the same future cash flows, explaining why immediate returns command premium valuations.

For retirement planning strategies, understanding the exponent helps you appreciate why starting early matters so much. Each additional year of time to invest (an increase in your exponent looking forward, though it decreases as you approach retirement) exponentially increases your wealth accumulation through compound growth.

Your personal finances improve when you recognize how the time value of money affects decisions from loan selection to investment choices. A longer loan term (higher exponent) means more total interest paid. A longer investment period (higher exponent looking forward) means greater compound growth.

The Mathematics Behind the Exponent: Deeper Understanding

For those interested in the mathematical foundation, the exponent’s power derives from how compound discounting works. When you calculate (1 + r)^n, you’re essentially multiplying the discount factor by itself repeatedly:

(1 + r)^n = (1 + r) × (1 + r) × (1 + r) × … (n times)

This repeated multiplication creates the exponential effect. Each additional multiplication (additional period in the exponent) doesn’t add a fixed amount; it multiplies the entire existing result. This is what makes exponential growth and decline so powerful in finance.

This exponential relationship explains why financial professionals often focus heavily on getting assumptions right for near-term cash flows while paying less attention to distant ones. A 1% error in year-5 cash flow estimates produces far less impact on present value than a 1% error in year-1 estimates, because the discount factor grows exponentially with the exponent.

Conclusion: The Exponent’s Critical Role in Financial Analysis

The exponent in the present value formula represents far more than a simple mathematical notation. This variable determines how aggressively you discount future cash flows and directly influences every financial decision relying on present value calculations.

By fully understanding that the exponent equals the number of compounding periods, recognizing how it interacts with the discount rate to create exponential effects, and appreciating its real-world applications across investment evaluation and financial planning, you’ve equipped yourself with essential financial literacy.

Your ability to make sound financial decisions improves when you recognize that time—captured mathematically through the exponent—is one of the most important variables in financial analysis. The exponent in the present value formula reminds us that money today is genuinely worth more than money tomorrow, and the further tomorrow extends, the more pronounced this difference becomes.

Whether you’re evaluating an investment, planning for retirement, assessing a loan, or making any financial decision involving future cash flows, the exponent ensures you properly account for the time value of money in your analysis.